Do you ever feel Uprooted? Armenians around the world know what it's like, and we're still learning to deal with the consequences.

Douglas Kalajian

______________

His great-grandparents fled the smothering Ottoman realm in the 19th century and the family settled in Egypt, where Goudsouzian was born. He was living in Canada, focused on his budding career as a filmmaker, when he became riveted by the turbulent events that led to Armenia’s renewed independence in 1991.

Goudsouzian felt compelled to go to Armenia in search of his “forgotten and sometimes ignored” identity. Nearly a quarter century later, he is still exploring the meaning of that identity—and, as his films show, he has plenty of company.

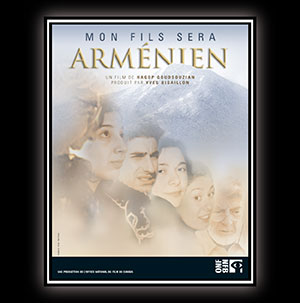

His first foray resulted in the documentary Armenian Exile. He followed with My Son Shall Be Armenian, documenting a trip to Armenia and Syria with other descendants of Genocide survivors.

His latest film, Uprooted, completes what he calls his Armenian Trilogy.

Along the way, however, Goudsouzian has explored the bond between Armenia’s culture and its national identity in other films, including this three-part Armenian Echoes series that details efforts to preserve Armenia’s musical heritage.

Goudsouzian’s films, which are available on DVD or pay-per-view streaming on HagopGoudsouzian.com, are marked by unusual intimacy and visual honesty. The viewer becomes part of the filmmaker’s conversations with folks he’s gotten to know and whom he clearly admires for their determination to survive as a people, not just as individuals.

These aren’t travelogues, carefully framed to showcase Armenia’s extraordinary beauty. We meet people with broken teeth but unbroken spirits, villagers who carry buckets of water up rocky hillsides and artists who carry the immense burden of capturing the spirit of a nation that is always so close to extinction.

I was engaged by Uprooted the moment I read the title. I think Armenians venerate their land more than most because they’ve been torn from it as well as torn apart from each other.

As Goudsouzian notes in the film’s opening, Armenia is home to only about a quarter of the world’s 12 million Armenians. How is it possible to sustain a culture when life in the Diaspora becomes the default? Clearly, the homeland must lead the effort. It is an extraordinary obligation for a poor country where mere survival demands great exertion.

Goudsouzian’s work suggests the effort required to perpetuate Armenian culture may be far greater than many of us in the Diaspora realize. We romanticize the homeland by imagining that our spirit springs from its soil, but culture is created and carried by humans. So the human loss suffered over the centuries inevitably drained Armenia’s cultural pool. As a result, Armenians have to repeatedly regenerate their culture in order to carry it forward.

One of the most interesting aspects of Uprooted is its exploration of the blurred line between the Diaspora and the homeland. In a very real way, Armenia is the Diaspora because much of the nation’s population is descended from Genocide survivors who fled East rather than West. One man speaks emotionally of coming from Sasun, now in Turkey, yet he eventually reveals that he was born after his family came to Armenia. What matters more to him is that he feels he is from Sasun, so he is compelled to relate the story of life in that time and place while keeping the memory alive.

I think the most challenging question raised by Uprooted and Goudsouzian’s other films is: What makes someone Armenian? No one offers a definitive answer, perhaps because there is none. But just about everyone acknowledges that the reality of our uprooted and scattered people is that identity can’t be based on birth place, or even language. Yet there must be more than just lineage if the Armenian identity is to survive in any meaningful way.

I know many who believe feeling Armenian is enough, but Uprooted suggests a more active role is necessary. Even if you don’t speak Armenian you can learn an Armenian song, or prayer. Cook something you remember from your grandmother’s table. Tell as much as you know of your family’s story to your children.

We are not like other people who have to search for their roots; we carry ours with us, because we have no choice. If we work at it, we can nurture them to take hold wherever we find ourselves in this world.

Apricot Armenian Gold (with Subtitles), Apricot Armenian Gold (with English Voices), Armenian Minstrels, Armenian Echoes (three part mini-series), Armenian Exile (also narrated).

Hagop directed and narrated the feature length documentary My Son Shall Be Armenian and Mon fils sera arménien produced by

the National Film Board of Canada.

He also produced and directed several shorts, A Taste of Armenia, on the famous Goom's Market of Yerevan, free on some DVDs and Blu-rays.

Recently Goudsouzian released UPROOTED (also narrated), Part three of his "Armenian Trilogy."

Goudsouzian is now developing a feature length documentary. To sponsor Hagop's new projects, use contact or sponsor links.

www.dougkalajian.com

www.dougkalajian.com

Canadian currency purchases are for Canadian residents shipped to a Canadian address ONLY.

Canadian currency purchases are for Canadian residents shipped to a Canadian address ONLY. US currency purchases are for US residents shipped to a continental USA address ONLY.

US currency purchases are for US residents shipped to a continental USA address ONLY. Euro currency purchases are for European residents shipped to a European address ONLY.

Euro currency purchases are for European residents shipped to a European address ONLY. Orders from other locations please

Orders from other locations please